photo (cropped) by Skiathos Greece on Unsplash

Housing has been identified as one of the key social determinants of health shaping the way people live and age. Ensuring adequate housing should therefore be a priority concern in our ageing society. But what are the challenges and barriers faced by older persons in accessing adequate and affordable housing? And are existing legal standards up to those challenges? Our recent contribution to a United Nations’ consultation can help get a clearer picture.

“Innovative housing, innovative transportation and innovative buildings programmes that make our cities accessible to all are urgently needed. Urban spaces have to be resilient and accessible to older persons, if we want to build inclusive, dynamic, resilient and sustainable cities and communities.”

Rosa Kornfeld-Matte, (former) United Nations Independent Expert on

the Enjoyment of all Human Rights by Older Persons, 1st October 2015

Age-friendly living environments are key element to support ageing well as they can help address number of issues in old age, such as independent living, autonomy and participation.

Aware of the importance of the issue, the Independent Expert on the enjoyment of all human rights by older persons, Dr. Claudia Mahler, has consulted interested parties in order to prepare her next report to the UN General Assembly on older persons and the right to adequate housing. This report will examine the existing international and regional legal standards applicable to older persons’ right to adequate housing; analyse the challenges and barriers faced by older persons in accessing adequate and affordable housing, including by exploring the interaction with other social factors such as gender, disability, sexual orientation, social status, place of origin and immigration status; and identify good practices.

Barriers to adequate housing in older age

Challenges, barriers and forms of discrimination faced by older persons in fulfilling their right to adequate housing are many and varied.

Ageism is a major obstacle that translates into different forms. It can be linked to negative stereotypes related to old age, for example our member in Czech Republic -Zivot 90 – highlights how owners tend to choose a younger tenant who, they believe, might be in better health and financial situation, and therefore more independent, flexible and less demanding. It can also be routed into the laws and policies, for instance older people are often denied access to loan to buy a property or to renovate their own home.

“At the present time though, a large part of homes and housing options in Europe are not fit for a wide range of users with specific needs and preferences. When living with a disability for instance, or when health declines and support needs arise, many people cannot find adequate solutions either to adapt their place, or to find an alternative option where they could remain autonomous while receiving the support they need.”

EU-funded project Homes4Life – 2019

Accessibility is another dimension of discrimination where ageism and ableism (age discrimination and prejudices linked to age and to disability) are closely interrelated. Indeed, the lack of accessibility impedes the right of older people to be independent and to choose where to live. The lack of accessible housing options and/or lack of financial support for necessary adaptations may contribute to the decision to leave the family home (and community) and enter a residential facility.

The choice to live where you wish can also be impeded by a reduced access to essential services such as healthcare or transport. This is often the case in remote and/or rural areas. Similarly, our members in Greece – Hellas 50+ – or in Portugal – Apre!- report back the pressure of gentrification in cities or of tourism on the housing cost forcing older people to leave their familiar living environment. Many of our members also underlined the rising cost of energy which puts older people in much greater risk of poverty if their dwelling is not adequately insulated.

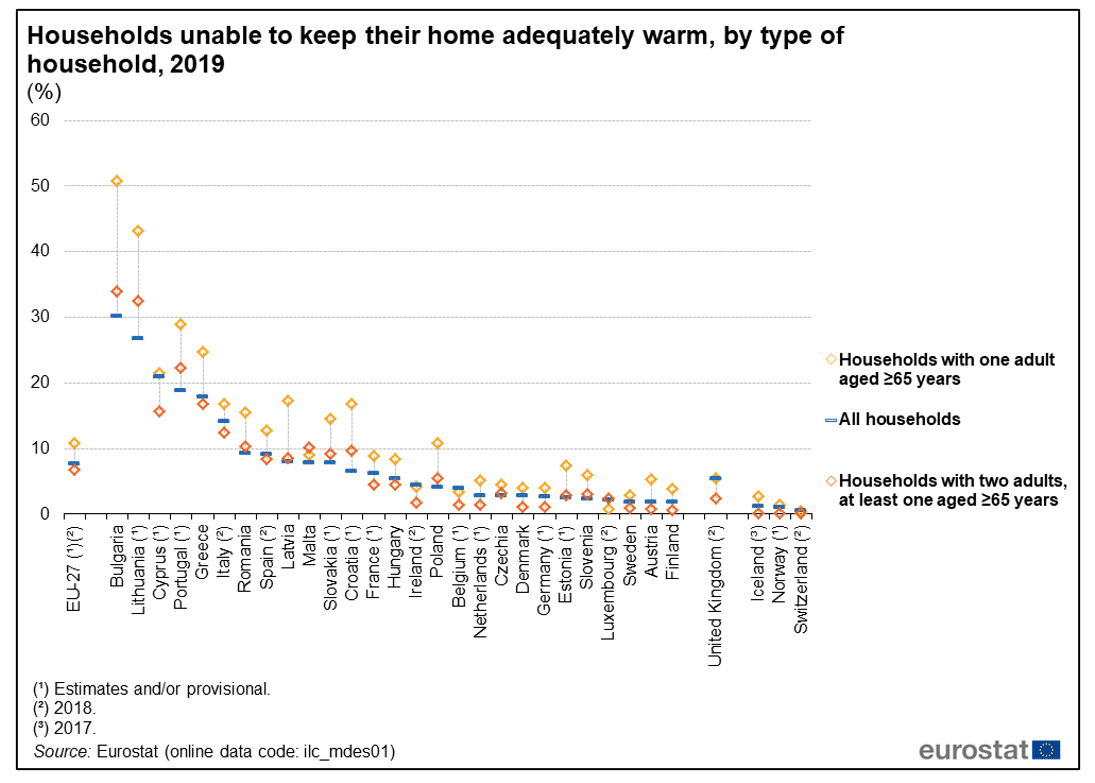

Older people living alone were more likely to be impacted by energy poverty[1]

These are only some examples bearing in mind that additional factors in older age can strongly impact the right to adequate housing. For instance, the so-called gender pension gap puts at risk the right to access adequate housing for older women. Older Roma’ rights are clearly at stake given that “30% of Roma are in households with no tap water and nearly 50% have no indoor toilet, shower or bathroom” (FRA Report 2016). For older people living in residential care settings, ILC-UK reports that residents with long-term physical and cognitive disabilities are at a high risk of isolation and exclusion in their housing environments due to physical and interpersonal barriers. They also often feel excluded from the on-site social activities in which they can’t easily participate, the inaccessible communications from staff or the physical design of schemes.

Looking to innovative alternative solutions

Despite the many challenges and barriers, there is a wealth of interesting examples which have been developed at local level.

To name only a few of them:

Netherlands: More than half of older people in the EU are living in under-occupied dwellings. As a response to this issue, the Vidome[2] housing association in the Hague (Netherlands) that has set up a special real estate agent for older residents to help them find more suitable accommodation in terms of size and/or adaptation.

Sweden: the Sällbo – community living project in Helsingborg[3], has turned a former retirement home into a vibrant mixed housing complex where half of the residents are over 70 and the rest are aged 18-25; all residents are committed to spending time socialising with their neighbours.

Belgium: the Calico project, developed by the Community Land Trust Brussels[4], was recently awarded EU funding under the Urban Innovative Action programme to create an inter-generational and socially diverse co-housing project built-in interaction with its neighbourhood.

France: association Delphis provides innovation services for social housing companies, including a specific label called ‘Habitat senior services’[5], which aims to increase non-dependent older tenants’ access to both adequate housing adapted to their needs.

Germany: In Saxony, the Association of Saxony Housing Cooperatives (VSWG) have developped a key concept namely “Die Mitalternde Wohnung” (“The home ageing with you”)[6].

Spain[7]: Zaragoza, Vivienda Housing Programme for older people with three initiatives focusing on older people:

- Centro Comunitario Oliver is a set of 38 apartments and a community centre. This is a project for senior citizens, aimed at people who are highly self-sufficient, living in adapted apartments, benefiting from services provided by the council as described below and sharing events and cultural/recreational activities with neighbours;

- Apartamentos Tutelados is a mixed-use building with 14 small adapted apartments and a community centre providing a range of services;

- Comparte Vida is a building with three apartments (three beneficiaries per dwelling) next to a council care home.

Italy : With the support of Ministry funding to tackle severe marginalization, some cities such as Savona, Bergamo, Siena and Biella, Rome have launched Housing First and Housing led services also for homeless people over 65 years. Thanks to the Housing First project and intensive support in site, it was possible to obtain their registered residence, family doctor and social pension.

Strengthening the right to adequate housing thanks to the legal and policy framework

In order to make the right to adequate housing a reality for all, it is important to also look at the legal and policy environment. Several EU legal and policy frameworks promote the right to adequate housing of older persons. This is the case for instance of the EU Charter Fundamental Rights[8] with the Article 25 on the rights of older people; and the 34 which recognises the “right to social and housing assistance so as to ensure a decent existence for all those who lack sufficient resources (…)”. Likewise, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities applies to the European Union; therefore, provisions related for example to independent living and accessibility contribute to ensure the right to adequate housing for older people. The European Accessibility Act[9] also provides interesting legal hooks by covering some services and products especially in the sector of new technology. However, housing per se is left out of this legal tool making it quite limited. Finally, in addition to the key principles referring directly to older people, most of the rights and principles in the European pillar of social rights[10] are recognised equally, regardless of any ground for differentiation, including of age. This is the case, for example, concerning the right of “everyone” to: access to social housing or housing assistance of good quality (Principle 19); and access to essential services of good quality (Principle 20).

Yet, there is a major gap as highlighted by the Fundamental Rights Agency in her 2018 report[11]: “Unblocking the Equal Treatment Directive[12] should be a priority. This would extend protection against discrimination based on various grounds, including age, to areas that particularly matter to older people – access to goods and services, social protection, healthcare and housing”.

Ageing in place

The right to adequate housing in old age has been particularly challenged during the COVID-19 pandemic: the last two years have further highlighted the need for housing that allows everyone to age with dignity and for supportive measures to combat social isolation. Likewise, the dire situation in nursing homes has (re)opened support for a change of approach towards so-called ‘ageing in place’ policies.

Similarly, climate change and the increasing number of related disasters like fire, floods or extreme temperatures, as well as the impact of pollution (noise, air being it indoor or outdoor) are somehow ‘new’ dimensions to be considered in relation to the right to adequate housing.

For more information

- Contribution of AGE Platform Europe to the UN consultation on the right to adequate housing of older persons

- Contact person: Julia Wadoux, Policy Manager on Healthy Ageing and Accessibility, julia.wadoux@age-platform.eu

- Read also:

[7] The report of Eurofound,“Inadequate housing in Europe: Costs and consequences” (2016)