In December 2016 Families and Societies published a European Policy Brief on “Policies for families: Is there a best practice?”, co-authored by researchers Olivier Thévenon, Gerda Neyer – whom AGE interviewed some time ago – and Chiara Monfardini.

This Policy Brief explores whether, in a context of changing family patterns (new family forms, high divorce rates, childlessness, etc.), some welfare systems address the new realities better than others. In a European Union where diversity in family and social policies is high, analysing whether there is a “best practice” comes as a challenging and timely research goal.

The Brief distinguishes between three groups among OECD countries:

- Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden), where working parents have access to generous parental leave and widely available childcare services. This favours both labour market participation and access to high quality education and care for children from a very young age.

- English-speaking countries (Ireland, United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States), which provide weaker parental leave and financial support only to the poorer families.

- The Western continental and Eastern Europe group is the most heterogeneous. These countries focus more often on financial benefits – often of low level – than on services, with the exception of France, which provides good access to childcare and parental leave arrangements.

In order to address how each model addresses the new family realities, authors looked into three issues:

- Youth’s transition towards self-sufficiency

Young people face today greater difficulties to do the transition towards adulthood, due to negative economic prospects (less jobs and less stable), globalization and technological changes in production processes, among others. This means that they need to rely on the support of their families and/or the welfare state. Nordic countries offer the most generous support to young people to do this transition towards adulthood through cash benefits and also services. According to Thévenon, policies can facilitate the transition by preventing early school leaving, promoting work experiences while studying and by ensuring income security.

- Use of parental leave by parents and the consequences for the family

Leave for fathers exists in most European Union countries (20 out of the 28 EU countries), paid or unpaid; this tends to be much shorter than maternity leave, but the situation varies substantially from one country to another (in terms of length, transferability options between parents, etc.). In some countries leave is possible well beyond the moment of the birth, and it often includes a “mommy and daddy quota”, meaning that leave works on a “use it or lose it” basis.

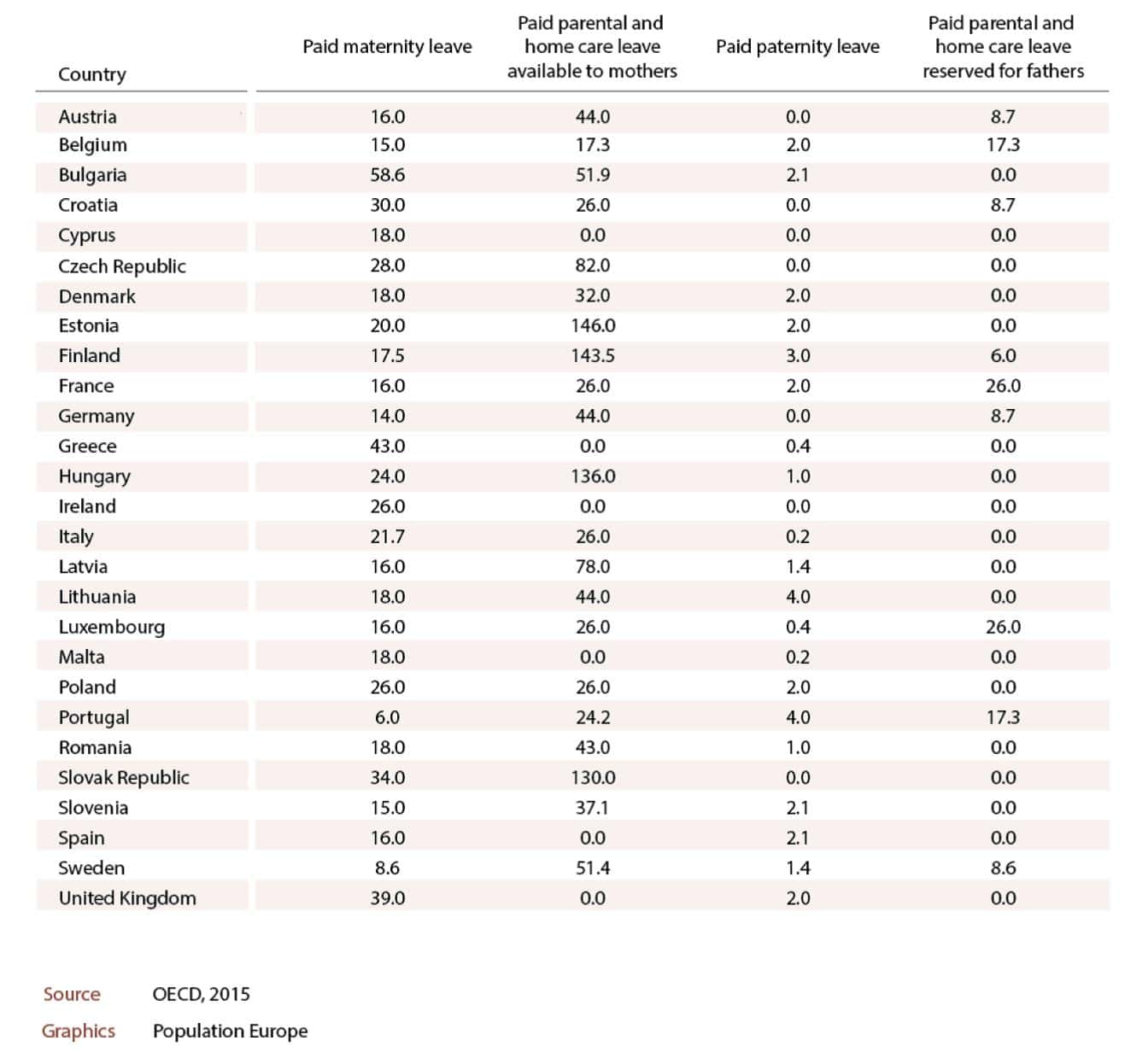

Length in weeks of paid leave entitlements available to mothers and fathers in EU Member States, 2015

As showed in the graphic, leave for fathers remains low. Moreover, take up is not full: paid leave (when this exists) represents often a serious income loss, and there is also a fear that taking up would increase risks in the labour market, especially among the less educated and those with less experience. However, the benefits of fathers’ taking up leave have proved to have beneficial effects in involvement of fathers in family live and household tasks. Other positive effects include more fertility and family stability. According to authors, these results support the implementation of parental leaves for fathers.

3. The effects of formal childcare on children’s development

Studies show that external high quality childcare is a good substitute of parental care and has positive long-term effects. It favours mothers’ participation to the labour market and reduces inequalities between children. Authors point out how ensuring access to childcare is a policy with the biggest investment dimension and preventative value over the life course. Whereas in Nordic countries, Portugal and Slovenia there is wide availability, this is limited in East, South and German-speaking Europe, which correlates with their low fertility rates and weak maternal employment levels.

The Policy Brief can be consulted here.